The City

Smithfield once blazed with burning martyrs.

An English boy of any education whatever knows that. During the days of Bloody Queen Mary, who hoped to restore a Catholic kingdom on our island, Protestants were burned by the dozens on stakes erected in Smithfield market, just outside the walls of London.

Of course, Mary had been dead these forty years and England was safely delivered from the Pope's clutches by our gracious Queen, Elizabeth. But Smithfield surprised me nonetheless. From childhood I had devoured Foxe's Book of Martyrs, with its bloody tales of the tortures inflicted on Protestants in this very place--I expected it to be grim or solemn. But when I topped the rise near the Red Bull tavern, a lively scene leapt into view--a clash of color and sound that appeared to jump up and down and wave like a flag under the clear April sky. It took my breath away. For a moment I stared, my heart pounding in my ears. Then I shifted my pack from one weary shoulder to the other and…

The City

Smithfield once blazed with burning martyrs.

An English boy of any education whatever knows that. During the days of Bloody Queen Mary, who hoped to restore a Catholic kingdom on our island, Protestants were burned by the dozens on stakes erected in Smithfield market, just outside the walls of London.

Of course, Mary had been dead these forty years and England was safely delivered from the Pope's clutches by our gracious Queen, Elizabeth. But Smithfield surprised me nonetheless. From childhood I had devoured Foxe's Book of Martyrs, with its bloody tales of the tortures inflicted on Protestants in this very place--I expected it to be grim or solemn. But when I topped the rise near the Red Bull tavern, a lively scene leapt into view--a clash of color and sound that appeared to jump up and down and wave like a flag under the clear April sky. It took my breath away. For a moment I stared, my heart pounding in my ears. Then I shifted my pack from one weary shoulder to the other and pressed on, with the sensation of plunging into turbulent waves.

My progress slowed as the crowd thickened and vendors pushed their wares at me: goodwives offering apples and sausages, noisy apprentices hawking every sort of useless trinket, a fishmonger who all but hit me over the head with a flounder. I hesitated before a pastry seller, moved on a few steps, drifted back, and finally laid out a half-pence from my carefully guarded hoard for a small meat pie. The seller would swear only that it was meat, and would not say what kind, but my hunger was such that I gobbled half of it straightaway, then wrapped the rest in my handkerchief. I had learned to stretch food as long as possible and besides, half was all I could hold. Five days of eating catch-as-catch-can on the road had shrunk my stomach to the size of a fist.

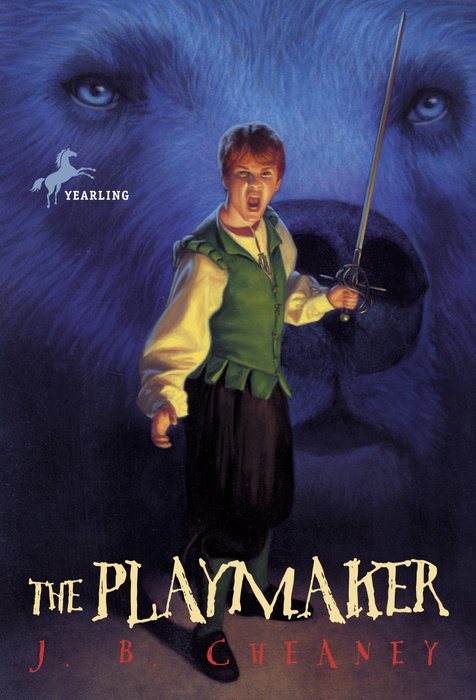

"The mighty Benjamin! A farthing will make him dance, good folk, only a farthing!" A lean man in leather made this cry in a hoarse voice as he twirled a red stick over his head. Looming shadow-like behind him stood the biggest bear I had ever seen, tied to a stout pole set in the ground. I stopped to gawk at him as a nursemaid with two squealing children in tow handed a farthing to his keeper. Then the beast turned his head my way.

His eyes caught and held me. A bear's eyes are black and tiny as beads, or so they appear in the vastness of a round, furry face. With his frayed leather collar attached to the chain that secured him, this one appeared more comical than dangerous: a grand-father of bears with dark brown fur silvered at the tips. As his keeper tapped the ground with the red stick, Benjamin shuffled through a lumbering dance, drawing a circle of onlookers. Once the performance ended, he took the nuts and crusts thrown to him with lordly indifference. But to me, he smiled.

Or perhaps the smile was only a fancy, for the moment I imagined seeing it, it was gone. But one thing sure: in the commotion of Smithfield market, in the shrill of vendors and din of penned-up livestock, it was me the beast sought out. The glint in those buttony eyes drew me in, and I was hardly aware of my own feet until I stood scarcely a yard from him. Then, quickly and without malice, he lifted a heavy paw and raked the knitted cap off my head. I felt the force behind that blow, and knew that only a slight shift in aim could have taken off my face. A rude laugh went up from the onlookers roundabout.

"Nah, nah, young master," said the keeper, easing me back with his stick, "Mind ye no' step too close. 'E's fiercer than 'e looks, aye, Benjamin? Give yon lad his covering back."

The bear had set my cap on his own head, to the vast amusement of the crowd. My face burned, for I realized I had been cozened into the show.

"Here, Benjamin." The laughter died as my voice rang out, steady as nerves alone could make it. A quarter of the meat pie trembled in my outstretched palm; his nose twitched as the smell reached it. "Swap my cap for what's of more use to you, and let us be friends."

The offer met with approval, both from the bear and the onlookers. "There's a bold lad," ran the general refrain, while Benjamin gently cadged the morsel in his cracked yellow claws and suffered the cap to be lifted off his head by his keeper's stick. The man renewed his cries in praise of "The mighty Benjamin! A farthing will make him dance. . . ." I adjusted my pack again and gave the bear a last look. But his eyes were restless, already seeking out another cap to lift from an unwary head.

Directly before me loomed the thick gray walls of the city and the towering arch of Newgate. A stony chill fell upon me as I passed through the gate, trailing its long finger down my back as I moved out of its shadow. Then I stepped into a broad swathe of sunlight and blinked with amazement, overcome for the moment. I had arrived: this color, this clamor, this dust, stink, and roar, was London.

As I gazed around me like an idiot, a hard object struck the side of my head and bounced on the cobbled street. It was a piece of biscuit, as hard as any stone. "Ahoy, green lad!" called a coarse voice above my head. I glanced up to a row of narrow, barred windows, where a hand on a hairy forearm was waving. I could scarcely make out a face in the shadows. "You want a job?" Immediately the neighboring windows thronged with the thieves and ruffians of Newgate Prison, beseeching me to fetch them nuts and cheese and pints of ale, jeering when I shook my head and backed away. "Watch your feet, boy," shouted one, "or we'll look to see you here with us!"

Such warnings were wasted on me. Though poor, I was well brought up and incorrigibly honest. Or so I thought at the time.