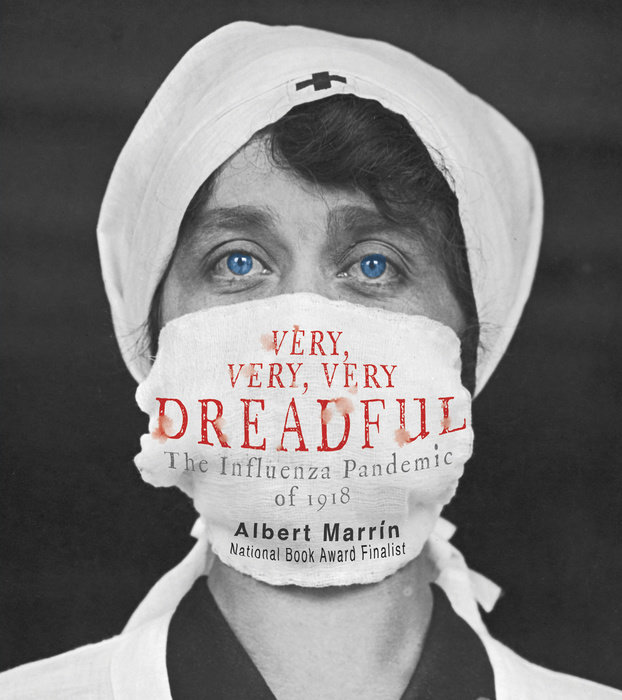

Very, Very, Very Dreadful

Author Albert Marrin

Very, Very, Very Dreadful

From National Book Award finalist Albert Marrin comes a fascinating look at the history and science of the deadly 1918 flu pandemic--and its chilling and timely resemblance to the worldwide coronavirus outbreak.

In spring of 1918, World War I was underway, and troops at Fort Riley, Kansas, found themselves felled by influenza. By the summer of 1918, the second wave struck as a highly contagious and lethal epidemic and within weeks exploded into a pandemic,…

From National Book Award finalist Albert Marrin comes a fascinating look at the history and science of the deadly 1918 flu pandemic--and its chilling and timely resemblance to the worldwide coronavirus outbreak.

In spring of 1918, World War I was underway, and troops at Fort Riley, Kansas, found themselves felled by influenza. By the summer of 1918, the second wave struck as a highly contagious and lethal epidemic and within weeks exploded into a pandemic, an illness that travels rapidly from one continent to another. It would impact the course of the war, and kill many millions more soldiers than warfare itself.

Of all diseases, the 1918 flu was by far the worst that has ever afflicted humankind; not even the Black Death of the Middle Ages comes close in terms of the number of lives it took. No war, no natural disaster, no famine has claimed so many. In the space of eighteen months in 1918-1919, about 500 million people--one-third of the global population at the time--came down with influenza. The exact total of lives lost will never be known, but the best estimate is between 50 and 100 million.

In this powerful book, filled with black and white photographs, nonfiction master Albert Marrin examines the history, science, and impact of this great scourge--and the possibility for another worldwide pandemic today.

A Chicago Public Library Best Book of the Year!

An Excerpt fromVery, Very, Very Dreadful

I

The Pitiless War

Infectious disease is one of the great tragedies of living things--the struggle for existence between different forms of life. . . . Incessantly the pitiless war goes on, without quarter or armistice.

--Hans Zinsser, Rats, Lice and History, 1935

Visitors from the Deep Past

For untold generations, before the invention of written history, people lived in small bands of relatives numbering, at most, a few dozen members. Our distant ancestors were merely creatures among other creatures, struggling to survive in an untamed wilderness. Called “hunter-gatherers” by modern social scientists, they were nomads, wanderers, people without a fixed place to live or call home. Each band had little contact with other bands, going from place to place, hunting animals and gathering roots, nuts, berries, and fruits to eat.

Unable to preserve or store food, nomads had to move continually, and on foot, to find their next meal. Without the wheel, a later invention, they also lacked draft animals; they kept no animals, except dogs, used for hunting and, in a pinch, for a meal. They carried their few possessions strapped to their…

I

The Pitiless War

Infectious disease is one of the great tragedies of living things--the struggle for existence between different forms of life. . . . Incessantly the pitiless war goes on, without quarter or armistice.

--Hans Zinsser, Rats, Lice and History, 1935

Visitors from the Deep Past

For untold generations, before the invention of written history, people lived in small bands of relatives numbering, at most, a few dozen members. Our distant ancestors were merely creatures among other creatures, struggling to survive in an untamed wilderness. Called “hunter-gatherers” by modern social scientists, they were nomads, wanderers, people without a fixed place to live or call home. Each band had little contact with other bands, going from place to place, hunting animals and gathering roots, nuts, berries, and fruits to eat.

Unable to preserve or store food, nomads had to move continually, and on foot, to find their next meal. Without the wheel, a later invention, they also lacked draft animals; they kept no animals, except dogs, used for hunting and, in a pinch, for a meal. They carried their few possessions strapped to their backs or lashed between two wooden poles, which the women dragged along the ground. The able-bodied men walked ahead, armed with clubs, stone-tipped spears, and bows and arrows, eyes peeled for danger or for game to pursue. Camps usually were just overnight stops to eat and sleep. But if the hunting in an area was good, the band might stay for a few days longer to butcher a kill, fill their bellies, and rest up for the trek ahead.

Hunting accidents, wounds, falls from trees, feuds within a band, and clashes with other bands took a steady toll. Still, the nomadic lifestyle had one advantage: it limited the impact of infectious diseases carried by animals.

All types of living beings have diseases that afflict them alone. Sometimes, however, a disease attacking one life-form “crosses over” and infects another life-form. Ancient nomads did not live amid heaps of rubbish, their own waste, and polluted water. After a few days at a campsite, they moved on, leaving behind any disease-causing microbes that might be around. If a disease crossed over to, say, a hunter, he might die. The disease might even infect the entire band, killing everyone. But that would be the end of the disease; it stopped when there was no one left to infect. It could flourish only by becoming a “crowd disease,” infecting a population large enough to allow victims to pass it to the healthy.1

About 11,000 years ago, humankind reached a critical turning point. Across the world, big game animals--mastodons, giant sloths, and saber-toothed tigers--became extinct, probably due to over-killing by the hunters themselves. Naturally, as food became scarcer, nomads sought other ways of feeding themselves. Many began to experiment, growing wild plants like wheat, barley, and rice for food. They also learned to domesticate wild animals; that is, to tame and raise them. Cattle, horses, oxen, sheep, goats, pigs, ducks, geese, and chickens: all became important food sources, and some, like horses and oxen, became work animals.

This turning point, called the Agricultural Revolution, placed new demands on people. Above all, it required the cooperation of several groups living close together. Of necessity, hunter-gatherer bands settled into permanent communities when they took up farming. With a larger, more reliable food supply, their numbers grew. Over the centuries, individual farms linked up to form villages, villages grew into towns, and towns into cities. The first cities arose in the fertile valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is today Iraq, and along the Nile River in Egypt, the Indus River in India, and the Yellow River in China. Farming and cities later emerged in the New World, chiefly in Peru and Mexico, based on crops like maize and the potato.

Civilization is the product of cities. Farmers usually grew more food than they needed, and the surplus gave others the leisure to do other things. Craftspeople, artists, priests, architects, engineers, and astronomers thrived. Over the centuries, they invented writing and mathematics, studied the sky, and created the calendar, which enabled farmers to plant and harvest at just the right times. Eventually, rulers raised armies and created empires to expand their domains.

The Agricultural Revolution, however, was a mixed blessing. Author Jared Diamond has even called it “the worst mistake in the history of the human race.” Agriculture, Diamond argues, was harmful to health in several ways. Archaeologists, scientists who study early peoples through their physical remains and the things they built, have found that more food did not always mean better nutrition. Preserved teeth and bones show that the common people, the vast majority, were less healthy than their hunter-gatherer ancestors. A largely plant-food diet is high in sugars and starches but low in proteins, the chemical building blocks of life. This meant that the masses of farm-folk were shorter than their ancestors--down from an average of 5'9" to 5'3" for men, and from 5'5" to 5'1" for women. Hunter-gatherers also lived longer, up to about forty years. Because of their diet and longer hours of strenuous work, farmers were usually old at twenty-five and dead by thirty.2

Yet there were other culprits. To clear the land for planting, farmers cut down forests, plowed the soil, and dug irrigation canals. These activities displaced native bacteria from their environments, where they were harmless to humans, and created pools of stagnant water, breeding places for disease-carrying mosquitoes. Irrigation canals also allowed microscopic worms such as blood flukes to enter the bodies of anyone who walked in them barefoot. Dried worm eggs have been found in Egyptian mummies 3,000 years old.3

Farm settlements became magnets for infectious diseases in other ways. Grain mills and storehouses attracted hordes of rats, mice, and insects. To make matters worse, farmers lived close to their animals--close to their feces, urine, blood, breath, blisters, vomit, sweat, sores, spittle, and snot. To discourage thieves, they might take prized animals into their homes. Farmers also collected human and animal waste to spread on their fields as fertilizer, or to tan hides into leather. Thus, by forcing people and animals to live close together, the Agricultural Revolution created ideal conditions for crowd diseases to take hold.

Close contact enabled the microbes that cause certain animal diseases to cross over to human hosts; hosts are living beings, animal or plant, on which or in which another organism lives. Today we share no fewer than 300 diseases with domesticated animals. For example, humans get 45 diseases from cattle, including tuberculosis; 46 from sheep and goats; 42 from pigs; 35 from horses, including the common cold; and 26 from poultry. Rats and mice carry 33 diseases to humans, including bubonic plague. Sixty-five diseases, including measles, originated in man’s best friend, the dog. We can still get parasitic worms from pet dogs and cats. That is why it is not a good idea to kiss a pet on the mouth or sleep with it in bed.4

Enclosed by high stone walls, with houses jammed close together along narrow winding streets, ancient cities were even more prone to crowd diseases than farms. Sanitation services did not exist, and drains flowed into the cobblestone gutters. City dwellers threw human waste into the streets, where it rotted, stank, and attracted vermin. Gutters ran with urine and liquefied manure. Stockyards and animal holding pens, usually located in crowded neighborhoods, swarmed with flies, fleas, and lice. Butchers slaughtered animals outdoors, in front of their shops, leaving puddles of blood; waste like brains and guts wound up in streams used for washing and in drinking water. So it is no accident that, for thousands of years, animal-borne diseases killed more city dwellers than were born each year. For that reason, cities needed a steady inflow of immigrants from the countryside to bolster their populations. Country-folk came seeking adventure and opportunity.

Civilization’s Plagues

All ancient civilizations suffered from infectious diseases that crossed over from animals. The Old Testament tells how the Lord threatened to send plagues to the Egyptians unless Pharaoh, the ruler of Egypt, released the Hebrews from bondage. When Pharaoh refused to change his mind, the Almighty caused “sores that break into pustules on man and beast.”5 Pus is a yellow-white liquid that the body produces during infection; it consists of dead white blood cells and bacteria.

The first detailed description of an urban plague comes from ancient Greece. In 430 B.C., the city-state of Athens went to war with the city-state of Sparta. When the Spartan army invaded Athenian territory, thousands of farmers from outlying villages fled to the fortified city with their livestock. Already overcrowded and filthy, Athens became even more so. Within days of the refugees’ arrival, a disease more terrible than anything ever experienced broke out. The historian Thucydides, an eyewitness, described how Athenians died horribly, the sickness beginning with “violent heats in the head,” followed by furious coughing, vomiting blood, and finally severe diarrhea. The Plague of Athens killed young and old, slaves and freemen, generals and common soldiers. “The bodies of dying men lay one upon another, and half-dead creatures reeled about the streets and gathered round all the fountains in their longing for water,” Thucydides wrote. By the time the plague ended in 427 B.C., one in three Athenians had perished.6

Modern scientists have not determined the cause of the sickness. Whatever it was, it set the pattern for future mass disease-events. As it raged, hysteria spread, the Athenian economy collapsed, family loyalties broke down, friends abandoned friends, and many expected the end of the world. The medical profession stood by, puzzled and helpless. In desperation, physicians devised “preventatives” and “cures,” which had no effect. The idea was to seem to know what to do--to do something, no matter how absurd, to try.

Centuries later, the capital of a vast empire, too, suffered from a mysterious plague. Rome, jam-packed with people and animals, was a city of luxurious villas of the rich and three-story apartment houses packed with the poor, the overwhelming majority. Disease was a regular visitor, even to the wealthy. The worst outbreak, known as the Antonine Plague, lasted on and off from A.D. 166 to 180. At its height, the disease took 2,000 Roman lives a day. It buried two emperors and wiped out nearby farming communities. Modern scientists are uncertain about its cause, except that it surely spread to people from domesticated animals.7

Dreadful as the Plague of Athens and the Antonine Plague were, they did not compare to the Plague of Justinian. Named for the emperor Justinian, who ruled the eastern part of the Roman Empire, it began in Constantinople (today’s Istanbul, Turkey). From there, between A.D. 542 and 547, it swept across the European and African lands bordering the Mediterranean Sea.

Constantinople saw the first recorded outbreak of bubonic plague. The term bubonic comes from buboes, swollen areas big as hens’ eggs that appear on a victim’s neck and groin, and also in the armpits. Symptoms include high fever, pounding headaches, delirium, and foul-smelling pus that escapes when a buboe bursts on its own or when a surgeon cuts it open. Often blood vessels rupture and blood leaks under the skin, forming black bruises, thus the plague’s other name: the Black Death.

The disease originated somewhere in Central Asia, moving along the trade routes connecting Asia to the West. It is caused by Yersinia pestis, a rod-shaped bacterium that lives in the guts of fleas. The fleas, in turn, live on rodents, particularly rats. Rats are key, because they infest people’s homes, barns, and storehouses. Fleas feed on blood, and when an infected flea bites a rat, it injects its bacteria-tainted saliva. Before long, the infected rat dies of plague; dead rats lying in the open are sure signs that plague is in an area. Like the bodies of all warm-blooded animals, rats’ bodies cool after death. Since fleas hate cold, they seek other, living rats to live on and bite. If none are available, they settle for the next-best thing--humans.8

The Plague of Justinian blazed through Constantinople like fire in dry grass. One survivor, the historian Procopius, claimed that some 10,000 people died each day--so many that gravediggers could not keep up with burials. In desperation, Emperor Justinian had the roofs of the stone towers that were built at intervals along the city’s walls torn off and corpses thrown in, filling each in turn. Procopius recalled, “The whole human race came near to being annihilated. . . . [The plague] embraced the entire world, and blighted the lives of all men.” Constantinople’s best physicians were stumped, for “in this disease there was no cause which came within the province of human reasoning . . . [and] no device was discovered by man to save himself.” The epidemic finally ended, no doubt because it ran out of vulnerable victims.9

Bubonic plague did not return for another eight centuries. The new epidemic, the worst ever, seems to have begun in China around the year 1342, then spread westward along overland trade routes and by sailing ship. From 1347 to 1352, it surged across the continent of Europe, reaching every country.

Fourteenth-century European cities were pestholes--filthy, animal-filled, and rat-infested. As in the first cities, people threw garbage out their windows; as a courtesy, they might shout to pedestrians, “Heads up!” or “Look out below!” Paris, continental Europe’s largest and grandest city, stank like a latrine. We get a hint of this from an odd fact: Parisians named streets for human wastes. Merde, French slang for “excrement,” described reality. There was the rue Merdeux, rue Merdelet, rue Merdusson, and rue des Merdons--Street of Turds. Paris also had the rue de Pipi--Piss Street.10

The royal palaces were no cleaner than the city streets. Since there were no latrines in the Louvre (today a famous art museum), noble visitors relieved themselves on the marble floors and under the grand stairways. To mask odors, the wealthy used perfume and wore small bags of dried flower petals around their necks. From the king on down, everyone had fleas. Some aristocratic ladies held small dogs on their laps to draw fleas away from their own bodies. Rats scurried about as if they owned the French capital and its magnificent buildings.

1. Arno Karlen, Man and Microbes: Disease and Plagues in History and Modern Times (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 21–23.

2. Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (New York: Norton, 1999), 95, 97; Jared Diamond, “The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race,” Discover, May 1987.

3. Karlen, Man and Microbes, 41.

4. Ibid., 39, 52, 57.

5. Exodus 9:14; Exodus 9:9.

6. “Thucydides on the Plague,” Livius, www.livius.org/pb-pem/peloponnesian_war/war_ t05.html.

7. Linda Gigante, “Death and Disease in Ancient Rome,” www.innominatesociety.com/Articles/Death%20and%20Disease%20in%20Ancient%20Rome.htm; Alison Morton, “The Antonine Plague--the Germs That Killed an Empire,” Alison Morton (personal website), alison-morton.com/2011/11/10/the-antonine-plague-the-germs-that-killed-an-empire.

8. Alexandre Yersin (1863–1943), a French physician, discovered the bacterium that causes bubonic plague in 1894. In 1908, researchers proved that rat fleas spread the disease.

9. Procopius, History of the Wars, Internet Medieval Sourcebook, “Procopius: The Plague, 542,” Fordham University, legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/source/542procopius-plague.asp.

10. John Kelly, The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), 17.