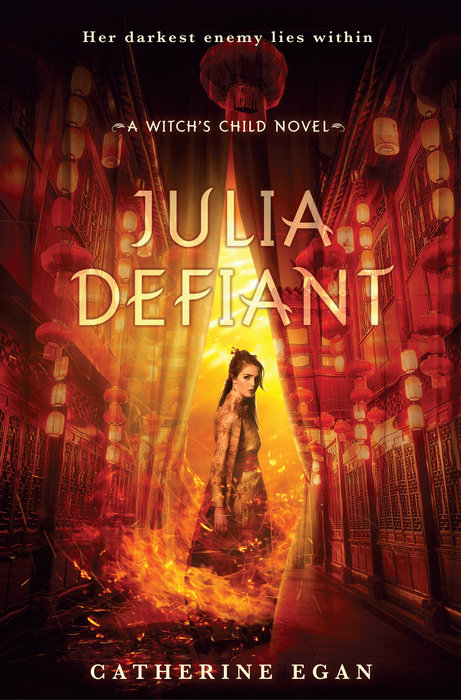

Julia Defiant

Julia Defiant is a part of the The Witch's Child collection.

Fans of Graceling and Six of Crows will thrill to the masterful world-building and fiercely flawed heroine in this heart-pounding follow-up to Julia Vanishes, book two in the Witch’s Child trilogy.

“Adventure, murder, romance, intrigue, and betrayal with a 16-year-old heroine that is both fierce and flawed at the same time.” —Hypable.com

Julia and a mismatched band of revolutionaries, scholars, and thieves have crossed the world searching for a witch. But for all the miles traveled, they are no closer to undoing the terrible spell that bound an ancient magic to the life of a small child. The evil, immortal Casimir wants that magic and every moment they hunt for the witch, Ko Dan, Casimir’s assassins are hunting them.

Julia can deal with danger. The thing that truly scares her lies within. Her strange ability to vanish to a place just out of sight has grown: she can now disappear so completely that it’s like stepping into another world. It’s a fiery, hellish world, filled with creatures who seem to recognize her—and count her as one of their own.

So . . . is Julia a girl with a monster lurking inside her? Or a monster wearing the disguise of a girl?

If she can use her monstrous power to save Theo, does it matter?

In this riveting second book in the Witch’s Child trilogy, Catherine Egan goes deep within the heart of a fierce, defiant girl trying to discover not just who but what she truly is.

Praise for Julia Vanishes:

“Egan’s debut novel sparkles. A beautifully rendered world and exquisite sense of timing ensure a page-turning experience.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review

“Readers will find themselves immediately immersed in the narrative and invested in the fate of Julia, who is both feisty and flawed.” —Booklist, starred review

“Julia’s a wonderful, fully realized heroine. . . . For those readers waiting for the sequel to Marie Lu’s The Rose Society, a well-realized page-turner in the same vein.” —Kirkus

An Excerpt fromJulia Defiant

One

When did I first go over a wall that was meant to keep me out? I don’t even remember. I’ve spent my life scaling walls. I’ve made a career out of what used to be just mischief--going where I am not supposed to go, seeing what I am not supposed to see, being someone I’m not. It has taken me farther from home than I’d ever imagined. This is a fine wall, tall and strong and tiled on top, and this is my third time going over it.

The sun set an hour ago, and the streets are already empty. I take a rope with a five-pronged hook at the end of it from my bag and step back a few paces, eyeing the wall and measuring the rope out. Then I give the hook a whirl and toss it up. It flies neatly, scraping against the stone on the other side and catching on the tiles at the top. I tug to make sure it’s firm and then walk up the wall, hand over hand along the rope. Straddling the top of the wall, I coil the rope around the hooked head and tuck it back into my bag.

From here I can see the whole city, the broad, paved streets and peaked rooftops surrounding the Imperial Gardens at the center. This is Tianshi, capital of Yongguo, seat of the greatest empire the world has ever known. Within these walls, in the northwest of the city, lies the Shou-shu Monastery, famous for its bronze bells and long-lived monks. It is a maze of dark temples and alleys around the Main Hall--almost like a miniature version of the city itself.

If I look east, I can see all the way to the Dongshui Triangle, the slum where my brother is hiding out with my ex-lover. I ate supper with them last night, and Wyn was in a poor mood. He’d had too much to drink and called me unforgiving, which seemed funny at the time.

I shoulder the bag with the hook in it and slide both my legs over to the monastery side of the wall. I’ve thought a great deal about forgiveness and what is forgivable. Still, I’ve yet to tell him I forgive you, because even though I have, he wouldn’t understand. When Wyn talks about forgiveness, he means having me back in his bed. It means something different to me. It means everything to me. It’s why I’m here, ten thousand miles from home, dropping from this wall onto the gravel path below.

Getting here was no small matter. We crossed half the world in two months, by ship and by train, by horse and by camel, by riverboat and by donkey cart and on foot. We saw wonders I never knew existed: the white palace floating on the lake in Beru, built for the king’s favorite concubine; the spiraling rock formations in the Loshi Desert; the Kastahor Mountains, cloaked in ice.

One evening, a few weeks into our journey, I found my brother, Benedek, sitting on the cooling desert sand, watching the sun setting behind the Eshriki Pyramids. Our tents and camels were just out of sight, over a dune. He smiled up at me and said something in Yongwen. This was Professor Baranyi’s rule, that we speak only Yongwen on the journey, and if he ever tired of giving us lessons on steamships or in bedsits, he didn’t show it. But I was having none of it here, alone with Benedek. To my chagrin, he’d proved a much more adept student than me.

“Can we just speak bleeding Fraynish for once?”

“You need the practice.”

“Well, I don’t want to practice with you.”

It was always a relief to be alone with him--really, with any of my own crew, but with Dek in particular. It was the only time I could be at ease. The rest of them--well, we were careful with each other, and I was conscious every moment of trying to win their trust, if not their friendship, and conscious too that they could never really trust me. Not after what I’d done.

“I was saying that they’re remarkable,” said Dek, gesturing at the pyramids with his good arm. “You know, the part we see is just the very tip of the pyramid, poking above the sand. The rest, underneath the ground, is absolutely vast.”

“Really?” I said, startled.

“No.” He snorted. “Pea brain.”

I punched him on the shoulder.

“Do you know what Mrs. Och said yesterday when she saw them?”

“What?”

“She said, ‘I remember when they built those.’ ”

He laughed. The sun sank behind the pyramids, the golden light that suffused the clouds and the sand and the pyramids themselves deepening to crimson. He asked me, almost casually: “Do you suppose they’ll forgive you if you find him?”

He didn’t need to explain who he meant by they or by him. But the question took me aback all the same. He’d clearly been waiting for a moment alone with me to ask.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Will you forgive yourself?”

“No.”

“I wish you could.”

“If wishes were horses,” I said, shrugging it off, and he let it go. We watched the light deepen and fade in silence.

The truth is that the question of forgiveness fuels my days and plagues my nights. Goodness was not something I gave much thought to until I relinquished any possible claim to it. Am I evil, as Frederick once suggested? There is no way to remake the past. The very best I can strive for, the work of every day now, is to be a good person who once did an evil thing.

If atonement also happens to be fun, well, that is just good luck. I land on the path and set off at a light jog behind the monastery library. The monks retire to their sleeping quarters at sundown, so I don’t need to worry about running into anybody. In my pocket, I have a wrinkled copy of the monastery map that Mrs. Och obtained for me. I’ve looked around enough to know it is inaccurate. Tonight’s task is to fill in the gaps. If some parts of the monastery are secret, unmapped, it’s a fair guess that that’s where I ought to be looking.

I make my way through the southern end of the monastery, avoiding the Treasury, the only place where guards are posted both day and night--not monks either, but proper imperial guards. There are three hundred–plus monks here, and they all look much the same to me, with their crimson robes and shaved heads, their gaunt, hungry faces. I am looking for one man: Ko Dan. This is complicated since I don’t know what he looks like or anything else about him besides his name and the fact that a year and a half ago he worked a terrible magic that needs undoing. Perhaps most important, I don’t know that he’ll want to be found.

The monastery buildings are made of ancient black wood from Yongguo’s northern forests, where the trees are black as pitch and a hundred feet tall. The rooftops are bright blue tile, though in the dark, they look as black as the wood. I turn right at the west wall, passing the sleeping quarters, several minor temples, the broad road leading to the Main Hall, and the elaborate Garden of the Elements, behind which lies a well-tended vegetable plot and a small house with a light flickering inside.

Three nights in a row, when the rest of the monastery is dark, there has been this one light. Through the window I see the same old man sitting at his desk, writing. His face is dark and wrinkled as a prune. He writes very quickly, as if agitated, page after page. He is wearing the crimson robe that all the monks wear, but he has a long braid down the back of his shaved head and a golden medallion on his chest.

When I told Mrs. Och and Frederick about the old man, they agreed it was probably Gangzi, elected leader of the Shou-shu Council. Anyone seeking to enter the monastery must obtain special permission from Gangzi, and my understanding is that this permission is so special it is never actually granted. Not even the emperor can come here unless Gangzi says so; the monastery is under Yongguo’s protection but not its jurisdiction. Women are expressly forbidden to enter under any circumstances, and I admit that just sweetens the job, as far as I’m concerned. For all that, it is easy enough to get in. Just a wall, and no guards besides those at the Treasury. Only the wrath of the empire and magic-using monks to worry about if I get caught, and I never get caught. Well--hardly ever.

The prune-faced man folds the paper, addresses it, seals it with wax, and adds it to a bamboo basket nearly overflowing with letters. He dips his brush and sets about writing the next one. I’d like to get my hands on one of those letters and see what he’s frantically writing about night after night, but I daren’t enter the little house while he’s there. I leave him to his work.

The Hall of Abnegation (Frederick’s translation) stretches the entire length of the northernmost wall. I pause between the hall and the swallow coop, tilting the map in my hand so I can catch a little of the moonlight to see by, when the ground shifts right in front of me. I step back against the wall of the swallow coop, stifling my cry of surprise.

A flagstone rises up from the path and is eased aside soundlessly. A shadow emerges from the ground, fluid and swift. The shadow replaces the flagstone without a scrape or a clink and slips away from me, down the alley. Talk about luck. I follow, heart galloping now with the thrill of the chase, even though I don’t know who or what I’m chasing yet.

We come to a wall about twice my height. Walls within walls within walls in this city. The shadow goes up and over it like a spider. I make a quick circuit of the wall. It forms a rectangle, fewer than two hundred paces right around, and there is a painted door facing south--locked. The wall is roughly made, the stones uneven enough that I can clamber up them easily, if not as smoothly as the shadow I’m stalking. I fling my leg over the top, lying flat to look down on the courtyard below.

At the center of the courtyard sits a modest house. Bamboo runs around the inside of the wall, thick and green. I see no sign of the shadow I followed here, but two figures are seated at a table in the candlelit garden. They are playing Zhengfu, a strategy game with tiles, similar to the Fraynish game of Conquest. The larger of the two figures is singing softly as she plays. So much for no women in the monastery. The tune is familiar--and then I catch a snatch of it and am shocked to realize she is singing in Fraynish. I know the song from my own childhood. It’s a depressing ditty about the weeping moon following the sun round and round, pulling her dark cape of stars behind her and longing for day. Why so sad, Mistress Moon, why d’you cry?

The other figure is so small I’d have guessed it was a child, except that she is smoking a pipe. She smacks down a tile, then scoops the singer’s tiles off the board with a little bark of triumph. The singer laughs and they rise to their feet. By her voice and posture, I reckon the pipe smoker to be an old woman.

The singer blows out the candles, and they head toward the house, the old woman carrying something long and bulky I can’t make out in the dark. I climb down the wall as fast as I dare, using the bamboo to steady myself, but the feathery tops of the stalks shake and rustle as I descend, and the singer looks back, calling out in Yongwen: “Is someone there?”

The old woman makes a beeline for me, and I realize she’s holding an old-fashioned blunderbuss. She pries between the bamboo stalks with it, the tip of the muzzle just skimming my shoulder. Her face is only a foot from mine, peering this way and that. It is a stern face, if slightly blurred from my perspective, with great scraggly eyebrows. She looks right at me, but she doesn’t see me, of course.

After checking the wall and the garden, she returns to the girl at the threshold of the house, and together they go inside, the girl casting a last look my way over her shoulder. I ease myself through the bamboo stalks and dash across the courtyard. They leave the door open to the chirping night insects, and so I slip in after them.

They pass through the main room to a smaller room sparsely furnished with a bed, a wardrobe, a dresser. There is a large wooden barrel to one side. The old woman takes the lid off, and steam pours upward from the hot water within. The girl is still humming her Fraynish tune, and by the lamplight, I can see her New Porian features, her fair skin and light-colored eyes. She cannot be much older than I am--eighteen or nineteen at most, I’d guess. She is thick-shouldered and plump, rather matronly in figure, but with a face ill suited to plumpness--too severe, with a small, pinched mouth and a long nose made comical by her round cheeks. She is dressed in a wide-sleeved robe of embroidered silk, like the upper-class ladies of Tianshi wear, her mousy brown hair held back with jade clasps.

The old woman says something I don’t understand, and the girl laughs again, breaking off her song. In spite of my weeks of immersive study with Professor Baranyi, now that I am here, I find everybody speaking far too quickly and not following the linguistic rules of Yongwen as I’ve learned them at all. It is difficult to catch more than a few snippets here and there.

The girl begins to undress. I’ve seen enough of the place, and it offends even my admittedly dinged sense of propriety to watch her take a bath, so I slip out to look for the shadow I followed here.

I find him outside, crouched on the roof, still as the night. I watch him for a few minutes but he doesn’t move, and so I go over the wall, more slowly and quietly this time, and run back to the swallow coop. I reenter the visible world, so that everything pulls sharply into focus around me, and search for the flagstone the shadow came out from under. At first I’m just breaking my fingernails on stones that won’t budge, but then I find the right cracks in the ground and pull it up.