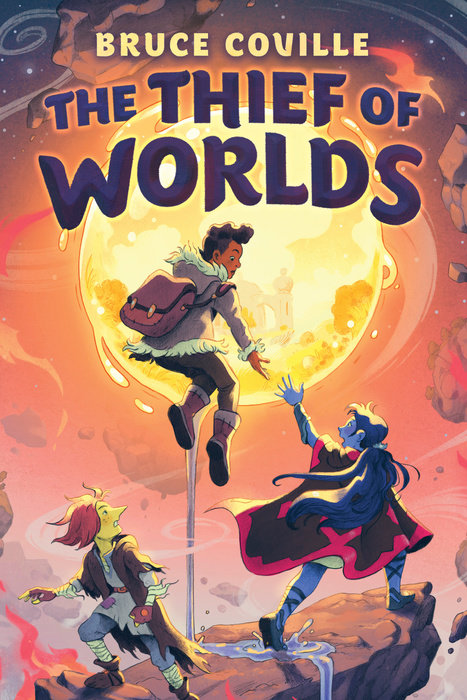

The Thief of Worlds

Author Bruce Coville

What happens when the wind stops?

The air grows hot and still and hard to breathe.

Hospitals fill with patients.

The world begins to panic.

What happens when the wind stops?

For Hurricane, this global disaster strikes at his core; but he must recover the magical horn that will fix everything.

Can magic be real? And how can it finding the horn rest on Hurricane's twelve-year-old shoulders?

This classic epic fantasy from beloved author Bruce Coville will enthrall readers while it…

What happens when the wind stops?

The air grows hot and still and hard to breathe.

Hospitals fill with patients.

The world begins to panic.

What happens when the wind stops?

For Hurricane, this global disaster strikes at his core; but he must recover the magical horn that will fix everything.

Can magic be real? And how can it finding the horn rest on Hurricane's twelve-year-old shoulders?

This classic epic fantasy from beloved author Bruce Coville will enthrall readers while it reminds them of the magic that lies in friendship and that friendship just might have the power to save the world.

For Hurricane, this global disaster strikes at his core. He got his name because he was born during a hurricane, and he has always felt a strangely intense connection to the wind. And now his mother is one of the sick people in the hospital. But what can he do? He's just a kid.

When all this turns out to be TRUE, Hurricane embarks on the adventure of his life: a journey to different worlds, where he will make friends unlike any people he has ever known. He will discover courage, strength, humor, and an ability to bring people together.

An Excerpt fromThe Thief of Worlds

1

My Strange Birth

The wind had stopped. Just stopped, as if someone had killed it.

Which meant that I was miserable.

Yeah, I know. Everyone in Chicago was miserable. And not only Chicago. The wind had stopped all across the world! For the first couple of days scientists had thought it was some weird coincidence. Now they were starting to freak out.

I was already freaking out. For me, losing the wind was like losing a best friend.

See, I’ve always had a thing for the wind. The people around me knew it. Back when Mom and Gran and I lived in Mississippi, the neighbors called me Breezeboy and laughed about how I danced with the wind. What they didn’t know was that the wind was talking to me. Okay, I could never really understand it. But I always felt it was simply a matter of time before somehow, some way, I would be able to.

Mom has a dish towel printed with the blessing may the wind be always at your back, and for me that has almost always been…

1

My Strange Birth

The wind had stopped. Just stopped, as if someone had killed it.

Which meant that I was miserable.

Yeah, I know. Everyone in Chicago was miserable. And not only Chicago. The wind had stopped all across the world! For the first couple of days scientists had thought it was some weird coincidence. Now they were starting to freak out.

I was already freaking out. For me, losing the wind was like losing a best friend.

See, I’ve always had a thing for the wind. The people around me knew it. Back when Mom and Gran and I lived in Mississippi, the neighbors called me Breezeboy and laughed about how I danced with the wind. What they didn’t know was that the wind was talking to me. Okay, I could never really understand it. But I always felt it was simply a matter of time before somehow, some way, I would be able to.

Mom has a dish towel printed with the blessing may the wind be always at your back, and for me that has almost always been true. When I was little, if I went outside, the wind would dance around my feet, then push me gently from behind as if it was playing with me. We even had a game, the wind and me. I would toss my hat in the air, and the wind would swirl it away . . . then carry it back and drop it onto my head. Once the wind even protected me from some bullies, rising from nowhere and blowing dirt into their eyes when they were about to pound me.

At least, I thought all that had happened. But that was when I was a little kid, so it was hard to be sure. By the time Mom and I moved to Chicago, after Dad was killed by that drunk driver, I had stopped thinking the wind was trying to tell me secrets. But my longing for it, my need for it, never ceased. Now that it was gone I was afraid I might go crazy.

On the third day with no wind Mom and I were in our apartment on the fourth floor of the Jerrold Arms. That name makes the place sound pretty classy, and maybe it had been when it was built about a billion years ago. Now . . . well, now it’s pretty run-down. Actually, “run-down” is too kind. Truth is, it’s kind of a dump.

It was early evening and it was hot. I glanced beyond Mom to our curtains. They hung limp and unmoving. God, how I wanted the wind to blow!

Mom was in her old red chair, mending a torn pair of jeans. The chair had been mended, too, since Mom had rewoven the places where the fabric had worn thin. “Too much throwing away, not enough fixing” was her take on the world. She was all about fixing stuff.

I was sprawled on the floor beside her, trying to draw. I was also complaining about the heat and the lack of wind. It wouldn’t have been so bad if we’d had AC, but we were way too broke for that.

“You should go outside,” Mom told me.

Without looking up, I said, “I could just crawl into the oven. It would be about as comfortable.” I didn’t look up because I was staring with annoyance at the spot where some sweat had dropped from my forehead onto the picture I was working on. I draw a lot, mostly fantasy creatures. Griffins are my favorites. I love their odd mixture of parts.

“The oven would be cramped,” Mom said. “Outside is bigger.”

She started to say something else but coughed instead, coughed that raspy cough that scared me. I jumped up to fetch her a glass of water. She took a few sips, breathing a little more deeply after each of them. When the coughing spell ended, I dropped back to the floor.

“Tell me the story,” I said.

“Aren’t you afraid you’ll wear it out?”

“Nah, it gets better every time you tell it. Besides, it’s about wind, so this would be a good night for it, since there isn’t any outside!”

She made a little snort. “It’s not just about wind, it’s about you. Maybe you should listen to other people’s stories now and then.”

As things turned out, I would be doing a lot of that before this was all over. But I didn’t know that then. All I said was “That’s why I like this one--I’m the only one who has it! Besides, you tell it good!”

“Tell it well, flatterer.”

I rolled my eyes. “If we can’t have wind, we can at least have a story about it.”

Mom picked up her mending and sighed. “Let me think for a minute.”

That meant yes. All I had to do was wait.

Sounds from the street filtered through our open window: a car alarm set off by some idiot; a girl blasting her boyfriend for being late; Herbie across the street practicing his drums like we weren’t all just about suffocating.

Mom began to cough again. The sound started in her throat, then spread until her entire body shook with spasms. The cough was already stronger than she was and getting worse each day that the air lay stagnant and still over the city. She leaned back and closed her eyes, her face pinched with the effort of trying to hide the pain. Her slender fingers trembled on the faded red arm of the chair. I reached up to put my hand on hers.

“How about that story?” she whispered.

“How about you just go to bed,” I replied.

She bopped me with the shirt she had been mending. “Who’s the mother here? I send you to bed, remember? And it’s too early for that. So zip your lips and listen.”

I smiled. “If you insist, Mother.”

“Hush,” she said, and gave my nose a tweak. Even though I had turned eleven back in May, she still liked to do that.

After the tweak she was silent for a moment. I closed my eyes, getting ready to listen. I had been practicing seeing the story in my head, trying to make it as real as possible, filling in new details every time I heard it.

Mom’s voice, soft but strong, led me into the picture.

It was back when we were living in Mississippi. We knew there was a storm coming, and your gran said it was going to be a bad one. Your gran had a way about that, about storms. She’d been watching the signs and getting more fretful every day. She had reason to worry, what with me pregnant, your daddy off to the war, and no one in town--which, I have to admit, was a few miles away--who much cared what might happen to us. Oh, that town! Never saw such people for minding their own business unless they thought there was a cent to be had in someone else’s. Dang pennygrinders knew there wasn’t any money to be had at our place, so they pretty much left us alone.

Wouldn’t have been so bad if the house wasn’t in such rough shape. But it was all we had, and your gran and I were glad enough of it.

It was Thursday, late summer. I was outside, taking clothes off the line, trying to get them down before the storm hit. The wind was high, and the clothes were whipping and whirling so much I was afraid I was gonna lose half of them before I could get back inside. So there I was, near to busting with holding you inside me, the wind wrapping the sheets around me so that I looked like a big white beach ball, when your gran comes running out and shouts, “Get in the house right now, Jessie! Leave the rest of the clothes! Ain’t safe out here. Storm’s getting close and we got to get settled!”

We had boarded up the windows the day before. Now we braced the doors with planks.

Lord, how that wind did blow! I heard it rise, and something inside me told me it was gonna be as bad as your gran said. Wasn’t long before it was howling around that old house, shaking the walls and making the timbers creak.

As if all that wasn’t enough, you decided that was a good time to be a-borning!

Your gran hustled me down the stairs to the cellar. Nearest hospital was forty miles away, and we didn’t have a car. But your gran had been bringing babies into the world a long time before I ever thought of having you. We took our lanterns and some food and some water down with us. Momma told me to sit tight while she went back upstairs to drag a mattress off one of the beds. She hauled it down the steps and pulled it into a corner. Then she made me lie down and told me to breathe real deep.

And all the while she was doing this, the storm was tearing at the house like a pack of wildcats screaming to get at us.

Things kept getting worse. You got more and more interested in being born, and that storm got more and more interested in blowing our house clean away. Me, I was lying there yelling and hollering, with your poor gramma washing my face and telling me, “Push, darlin’! Push to get that baby out!”

And still that storm kept getting bigger and louder.

Then the rain started. Honest to heaven, child, I doubt it bucketed down any harder the day Noah closed the doors on the Ark. And still the wind shrieked around the house as if someone was being killed right outside our window. Then the wind busted through . . . blew the boards right off one of those little cellar windows and sent glass flying all over the place!

And with all that going on, every minute you were getting closer and closer to being born.

The house started to shake. I could feel it shudder on its foundation as the wind smashed against it. We heard a terrible howl, like Lucifer falling from heaven, then a cracking sound, and then the house was gone. Gone! The wind ripped it right from over top of us, splitting it into boards and shingles and broken glass. The whole thing blew away like it was scraps of paper.

And that was the very moment you made your entrance!

So there we were, the three of us in that tiny cellar. The rain was pouring in. I was screaming because I thought I was going to die before I even got to know you, you were squalling because that’s what babies do, and your gran was trying to quiet both of us. Finally she snatched you up, leaned over you to protect you from the rain, and started yelling, “Help! Help!”

Shouting for help in the middle of that storm seemed pretty dang foolish to me. Except help came! I don’t know from where. I don’t know how. I don’t even know what it was. All I know is that even though the storm was still raging, suddenly the wind and rain were gone from the cellar. I saw a huge winged shape above us. And it wasn’t moving! Wind that could blow away a house whipped around it, and this thing just hung in the sky without moving!

Then a soft voice, a voice I could hear even with that wind screeching like a band of demons, whispered, “Rest. Sleep. You and yours are safe.”

The last thing I remember was two golden eyes staring down at me from the storm. Then I fell asleep. Asleep! How can a person fall asleep when there’s no roof, and a raging storm, and a brand-new baby, and something that shouldn’t even be up in the sky?

Your gran told me later that when she covered you up and laid you down beside me, a breeze danced around your head, tugging at the corners of the blanket. She said you looked happy and peaceful. So she kissed you, then named you, and that was the last thing she remembered from that night.

When she finished, I crowed, “And that’s why I love the wind so much!”

“That’s why, Hurricane,” she answered. “That’s why, my hurricane boy.”

2

Zephron

Two days later Chicago had moved from edginess to the border of panic. That’s not me talking. It’s what all the radio stations were saying. Not surprisingly, the internet chatter, which I kept checking at the library, was utterly bonkers.

It wasn’t just Chi-town, of course. People all over the world were flat-out terrified.

As for me, it was all made worse by the fact that Mom was getting sicker. She wasn’t able to get up at all now, so I stayed beside her bed to keep her company. I’m not sure that did any good. She could tell how upset I was, the way moms always can. Thing was, I knew it was only going to get worse. Despite the emergency restrictions on cars and trucks that the mayor had slapped down, with no wind to blow away the pollution Chicago’s air was getting filthier by the hour.

I did what I could to keep the apartment cool. But what I could wasn’t much--basically I kept a big bowl of ice cubes in Mom’s room, with a fan blowing across it. The fan’s speed went up and down because the city was having brownouts, since everyone who did have AC was using it full-time on high.

I was sick, too. Not sick like Mom and the others who were having trouble breathing. I was sick with fear for my mother. I was also sick in my soul. The wind had been my special friend since that crazy night when I was born. Now it had been snatched away without warning, without any way of knowing why or how.

Late that afternoon Mom reached up, took my hand, and said, “Hurricane, look at me.”

Her voice was ragged. I tried to hide how much it scared me.

“Listen to your momma,” she went on. “Stop worrying. There’s nothing you can do about this. Soon enough the wind will start up again. The bad air will blow away, and we’ll both feel--”

She was interrupted by the cough. She spit some blood into a tissue, then went on as if nothing had happened. “You’ll feel better. The city will calm down. Everything will be all right. So you should stop worrying.”

“And you should stop talking! It makes your cough worse.”

She sighed and turned her head away.

“Do you want some tea with lemon and honey?” I asked, desperate to do something, anything, to make her feel better.