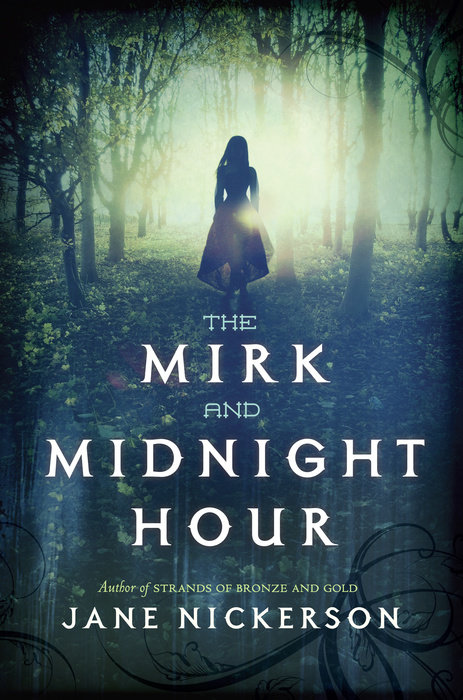

The Mirk and Midnight Hour

A Gothic thriller and captivating love story set in Civil War Mississippi

Seventeen-year-old Violet Dancey has been left at home in Mississippi with a laudanum-addicted stepmother and love-crazed stepsister while her father fights in the war—a war that has already claimed her twin brother. When she comes across a severely injured Union soldier lying in an abandoned lodge deep in the woods, things begin to change. Thomas is the enemy—one of the men who might have killed her own brother—and yet she’s drawn to him. But Violet isn’t Thomas’s only visitor. Someone has been tending to his wounds—keeping him alive—and it becomes chillingly clear that this care hasn’t been out of compassion. Against the dangers of war and threatening powers of voodoo, Violet fights to protect her home, her family, and the man she’s begun to love.

“An exciting story—juicy, romantic and at times quite chilling.” —BookPage

“An atmospheric story in which darkness houses mysteries, [with] rich imagery and imaginative subplots.” —Kirkus Reviews

“Compelling. . . . There’s a languid ease to the prose that invites readers to become fully immersed.” —The Bulletin

An Excerpt fromThe Mirk and Midnight Hour

"There are too many bodies," I said under my breath.

"Of course there are," Laney called from the other side of the wall. (She was keeping baby Cubby away from unpleasant sights. In case he remembered.) "And this is a drop in the bucket compared to how many busted-up soldiers there are. Y'all are going to wipe each other out before you're through. Why'd you need to come look at them again anyway?"

I ignored the question. "What I mean is, the count's wrong. Last night, when they first laid them all out and pinned their toes, there were only eighteen. Now there's nineteen." I shuddered as I brushed away a fly that tickled my forehead. Don't think about where it might have been. These men lying in the grim, gore-puddled courthouse yard, who had been carried out feet-first from the makeshift hospital inside, were dead less than twenty-four hours, yet the buzzing already sounded loud and angry within the blankets.

"Probably you counted wrong. You couldn't see so good in the dark. Or someone else died later and they brought him out. Whatever. It doesn't matter." Cubby whimpered and Laney sighed. "Come on. I've got to get home and feed this child."

It had been a long day for her. Bouncing and jiggling a fat baby was more exhausting than one would think. But I couldn't hurry away. A heavy sorrow weighted my legs as I paced slowly down the row of blanket-wrapped bodies laid side by side, waiting for the wagon to take them for burial. Each was somebody's tragedy.

"I counted right," I said. "I had a lantern and was careful. I copied down the dead men's names from their tags so I could say a prayer for each and in case no one else recorded them. And no one else was fixing to die soon. Dr. Hale assured me. That's why I thought I could leave after the other nurses came in from Mobile."

The yard hadn't always been grim. In former times, before the yellow hospital flag flew from the courthouse rooftop, deep pots of geraniums and marigolds had lined the walls. The containers were still there, most with shriveled, blackened plants drooping inside. Someone had tossed an amputated arm into an empty flowerpot. A freckled hand reached from it, looking so natural it was as if some farm boy crouched inside, about to clamber out. Once, I would have felt extremely queasy at the sight. However, the past intense days of nursing the wounded from the big battle near Shiloh Church, in Tennessee, had altered my sensibilities. I had knelt in enough pools of blood and bathed enough ragged red flesh to be only slightly queasy now.

I halted. "It's this one that's extra. No name." I squatted and started to pull back the covering.

Laney peeked around the corner and squealed. "Violet Aurelia Dancey! Stop that right now, you hear? You crazy?"

"I don't want to look. I just need to see if his name's inside so I can add it to the list. We'd never have known what happened to Rush if someone hadn't written him down." It had been two months since the arrival of our family's black-edged letter announcing the death of my twin brother. I hunched my shoulder to wipe my eyes against my sleeve.

Inside, no tag was attached to a shirt because this young man was naked. I quickly averted my gaze to meet his shocked, dead eyes, which no one had closed, staring up through a swarm of stubborn, engorged insects. The face was wide, flat, and waxy white, the hair a carroty orange. Somehow his homeliness made it worse. So ordinary--he could have been anybody. I gave a gasp and pulled the blanket over him again.

"See?" Laney said. "I told you not to look. And don't you go asking about this. We've got to get home."

"No," I said slowly. "I won't ask."

The death wagon rumbled up for its load, and Laney took up one split-oak market basket and handed me the other. I was trembling; I dropped it twice before grasping it firmly.

Rain had poured down earlier in the week, leaving the roads hopelessly sloppy. I followed dumbly, mulling over what I had just seen. As we squelched along, skirting mud puddles, I had to curl my toes to keep my boots from rattling around my ankles. They were too-big boys' boots--all I could find to buy when my old shoes were so worn out I was nearly walking barefoot.

The town of Chicataw was cradled in a hollow of meadow and field, ringed by sheltering, wooded hills. Our three-mile walk home led past long, dim stretches of woods and pecan groves, as well as cotton fields, where slow-moving workers were breaking the earth with hoes and picks. It was later in the day than I had thought. Long-fingered shadows reached across the road, and the trees loomed black as we passed through a grove.

"Miss Vi, you've got to stop poking round dead people," Laney said, breaking through my thoughts. "Look at you. White as a winding sheet."

I glanced around quickly and whispered, "It was--that body. His throat was cut ear to ear. Like another mouth in his neck." The words felt thick and sluggish as they rose from my throat. "That didn't happen in battle. Somebody murder-killed him, not battle-killed him."

"Stop that right now. You don't know anything. It could've happened in the fight."

"There was a red flannel bag tied to his neck."

Laney stopped in her tracks. "You're joking."

I shook my head slow and low.

"Conjuring," Laney breathed. "Somebody around here's doing hoodoo and they must've stuck that body with the others to get rid of it."

"Why not just dump it in the river?"

"Might be they think it's fitting to show respect for the corpse by returning it to its own folks after they use it for what they want."

Coldness slithered through my veins. "We should probably report it to the marshal before the body's buried."

"Uh-uh." Laney shook her head emphatically. "You tell and you bring those conjure folks down on us. You're not about to do something so plumb foolish. No, ma'am. There's some other reason for that body anyway--you saw wrong or something."

"I didn't see wrong."