CHAPTER 1

CRASH

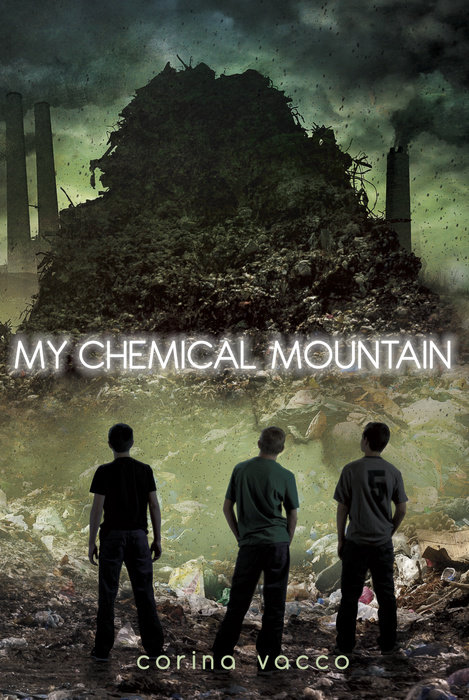

The wind carries sulfur and hard rain. Power lines are down in the streets. I trace the outline of a petroleum serpent on my foggy window and wipe it away with my fist. I think about the seventeen tons of Benzeflux that went missing the night Dad died. Green, steamy chemical sludge. Coveralls in a puddle of liquefied human skin. The horrible phone call that woke us in the night. I am hungry for revenge.

Last time there was a storm like this, me and Charlie hot-wired a dump truck and crashed it into the field of barrels. The time before that we started a small chemical fire in the creek, watched the water burn in the rain. Storms make us wild sometimes, like animals.

Mom calls to me from the kitchen. “Jason, where are you? Can you believe how bad it’s raining? I wish you wouldn’t hide away in your room all night. Come help me fold towels.” I can tell she’s eating something from one of her stashes. She has hidden bags of cheese…

CHAPTER 1

CRASH

The wind carries sulfur and hard rain. Power lines are down in the streets. I trace the outline of a petroleum serpent on my foggy window and wipe it away with my fist. I think about the seventeen tons of Benzeflux that went missing the night Dad died. Green, steamy chemical sludge. Coveralls in a puddle of liquefied human skin. The horrible phone call that woke us in the night. I am hungry for revenge.

Last time there was a storm like this, me and Charlie hot-wired a dump truck and crashed it into the field of barrels. The time before that we started a small chemical fire in the creek, watched the water burn in the rain. Storms make us wild sometimes, like animals.

Mom calls to me from the kitchen. “Jason, where are you? Can you believe how bad it’s raining? I wish you wouldn’t hide away in your room all night. Come help me fold towels.” I can tell she’s eating something from one of her stashes. She has hidden bags of cheese curls in the coat closet, pork rinds under an end table in the living room, chocolate-covered pretzels in a Christmas tin in the garage. Eating is her new tic, like a twitching eye or a stutter.

There is an explosion of thunder, the kind that sounds like it’s right on top of you, or maybe even inside you, and then my room goes dark. The ceiling fan stops spinning. The television blinks off. Charlie’s gonna be here any minute now. It’s just a matter of time.

Mom taps on my door. “It looks like you’re off the hook. I have a feeling the power’ll be out for the rest of the night. I’m going to bed.” She can be disgusting sometimes, spilling chunky beef soup down the front of her pajamas, falling asleep with potato chips in her mouth. I wonder what it feels like to wake up every morning as her—thirsty and still tired, crumbs on the pillow case, swollen fingers.

Charlie, where are you?

I lie on my bed and listen for cars on the 990. I have a short dream about blue spiders in an underground cave. Something rattles my bedroom window. My eyes snap open. My stomach is pulsing like a machine, painful pistons and gears. There is a siren in the distance. I grab an old sweatshirt and climb out my window. Slowly, silently.

Charlie is standing next to his dad’s new four-wheeler. It is blue and black with a wolf custom-painted on the front. It smells like gasoline and vinyl. We aren’t supposed to go near it.

“Think Randy can airbrush something like that onto my dirt bike?” I say. The rain is falling hard, like gravel on my face.

Charlie just looks at me. Maybe he notices the stains on my jeans: black spray paint and battery acid on the knees, mud everywhere else. Or maybe he’s looking right through me, his mind kicking around some kind of trouble at home.

“What’s your problem?” I ask. He’s seemed distracted a lot this summer, but the circles under his eyes are new.

He blinks and says, “I can’t sleep. I’m so tired, I’m not even tired.”

“I’m never tired,” I say. “I only sleep because it’s boring to stay up forever.”

Already my sweatshirt is wet and heavy. Charlie has on army-green rubber boots and a pair of welder’s goggles. I consider the black garbage bags we have in the garage, how easy it would be to turn them into raincoats.

Charlie’s scars look blue in the lightning. I sit on the back of the four-wheeler as he steers us away from our neighborhood. We take the old steel bridge across Two Mile Creek. We jump flooded ditches and skid onto empty highways. I lift my face to the sky and drink the rain. I taste motor oil on my lips.

The Poxton landfill looms up ahead, black and eerie on the horizon. Charlie calls it Chemical Mountain. To him it is one of the wonders of the world. If we could spend every moment there, jumping barrels on our dirt bikes or racing snowmobiles, he’d be happy. Cornpup, though, he calls our landfill the Nightmare. He spits on it, pees on it, swears at it—like a mound of chemicals and dirt can have hurt feelings or whatever. He hammers toxicity reports to his wall and says words like uranium, then watches our faces for a reaction.

When we pull up to Chemical Mountain, lightning strikes a nearby tree. My skin is buzzing.

Charlie kills the engine. “When I come here, I feel real strong,” he says. “Like I could pull down a bunch of electric wires and not get shocked. Like I could pick up a cement truck and throw it across a field.”

“I still think we should bottle the dirt, sell it,” I say. Then I feel stupid, because Charlie would never give away his secret. He eats handfuls of mud from Chemical Mountain. He swallows orange and green water from Two Mile Creek. He’s the only fourteen-year-old in Poxton who can catch a thirty-yard pass in triple coverage. His muscles are like steel coils under his skin. I’d eat anything to be like that, but I tried it once, and all I got was a rash of hot blisters on my tongue.

Thunder rips through the sky.

There is a chain-link fence at the base of Chemical Mountain. Charlie pitches rocks at the no trespassing signs while I pry open the gate with his crowbar. We ride to the top of our landfill, lightning all around us, the air so electric I feel dizzy. I squint because the rain is falling sideways, straight at our faces. From the summit we look down on a large rectangle of darkness—our street and the neighboring streets, still without power—and we feel like war gods, like we’ve conquered something for real.

“Drive fast,” I shout to Charlie.

As if he has to be told.

We fly down Chemical Mountain at full throttle. I think about how, two weeks ago, Mom missed my eighth-grade graduation. I came home to find her sitting on the kitchen floor, eating fried hamburger out of a casserole pan, holding her spoon like a shovel. I grabbed her ceramic turtle from the windowsill and smashed it against the tile. I would’ve broken more than just a turtle if Charlie hadn’t walked in. He swept up the mess, and Mom belched silently, and I wanted to pack a suitcase and take off. Except I don’t have anyplace to go.

The thing is, she wasn’t like that when Dad was alive.

My nose is bleeding again. I don’t like to bleed the way Charlie likes to bleed. It’s not a badge of honor to me. I wipe the blood on my sleeve. Neither of us thinks about the large metal vents that release gases from the landfill’s belly. We want the rush, the thrill of speeding without limits, without lights, without anyone to stop us.

Halfway down the mountain, I hear a horrible sound, like a chain saw cutting through steel. The four-wheeler flips and rolls. I fly twenty feet, and my shoulder pops when I hit the ground. Pain shoots through me, but I do not cry out. There’s mud in my eyes. I hear Charlie shouting—“Are you okay? Are you okay? Are you okay?” It’s so like him to injure his wrist and ignore it, to worry about me instead. I don’t tell him I landed next to a damaged vent that’s reaching up through the weeds like a tiny sword. I think about the sandwiches at Tavern on the Creek. White bread and turkey and tomato and cheese with a toothpick stabbed straight through the middle.

That could’ve been me.

We stand over the ruins of the four-wheeler for a long time. The custom-painted wolf is crunched up, all that detail, just . . . gone. Dark liquid is dripping from the engine. Charlie is jamming his fist into his thigh, like he’s already formulating a plan. He says he’s gonna mess up the garage and make it look like a burglary, like the four-wheeler got stolen. I don’t understand how he will explain his swollen wrist.

“You worry too much,” he says.

We take a bold shortcut home, trespassing on Mareno Chem’s property, knowing that if we get caught, they’ll press charges. The parking lot is empty except for a shiny silver Lexus. A slimy liar owns that car. I wish I had the guts to slash his tires. Or worse.

We enter mudflat territory. It’s hard to walk with the ground sucking at our shoes. I lead Charlie up and over a rugged, uncapped landfill, which is a mistake, because he finds a dead red-tailed hawk, its wings all soggy, and he makes me dig a hole in the wet garbage with his crowbar so we can give the bird a real burial. Just beyond the landfill is our high school. The sight of it makes me want to puke my guts out.

Charlie says, “See the football field? That’s all fresh turf they’ve got there. I’m gonna get new cleats before tryouts. I’ve been real disciplined about saving my money.”

High school will be easy for Charlie, because everyone likes him—plus he’s a badass football player. High school will probably be easy for Cornpup too, because he’s the type who doesn’t care what people think, and there’s so much freedom in that. I’m the one who’s scared. I’m the one who’s not ready. What if me and my friends drift apart in a big school? We could end up in different classes or get swallowed by totally opposite groups of friends. I feel the end of summer chasing me, snapping its jaws at my heels.

“I’m starving,” says Charlie. “I have to eat soon or I’m gonna die.”

Charlie’s dad can bust holes through a wooden door with his bare hands. One firecracker snap of his leather belt and you’re bleeding. It’s the whisky. It’s the economy. It’s always something.

“Your old man’s gonna kill you when he finds out you destroyed the four-wheeler. You can crash on my floor tonight if you want.”

“He won’t find out. I’ve got it covered,” Charlie says, spitting blood into a puddle. “Anyway, my mom went shopping after work. We’ve got blueberry waffles in the freezer.”

Later, maybe tomorrow, Cornpup will yell at us for not dragging the four-wheeler home. He will walk all the way to Chemical Mountain to examine the twisted machine. He’ll fill a giant duffel bag with things that mean nothing to Charlie and me: hinges, strut springs, cables and belts, rotary valve parts, and a motor mount. It’ll take him weeks, and it won’t be pretty—bodywork is needed, and a new paint job—but he’ll get the four-wheeler running again, its motor purring like new. I give him credit for seeing potential where I see only a hopeless mess. I wish he knew how to bring people back to life.

It’s not fair that my dad, a man who wouldn’t even plug in a table saw without safety gloves, is dead. He was a drummer and football player. He followed the rules. He picked up some overtime hours at the chemical processing plant, just wanted some extra cash, and now they say the accident was his fault. Being good didn’t get him anywhere. Playing it safe didn’t earn him extra points. He could’ve been a skydiver or a junkie or a stuntman. It wouldn’t’ve mattered.

Charlie says it’s hard for kids to die, that it’s almost impossible, but I saw Joe Farley the day he puked all over the Pelliteros’ sidewalk. He’d gone swimming in Two Mile Creek when the water smelled like melted plastic, and anyone with half a brain knows that the colored water is fine, that it’s the smelly water you have to stay away from. His eyes were all bloodshot. I asked him if he was okay, and he said I should “piss off.” Later that day he fell from the window of the abandoned rubber factory on Grant Street. I’ve been in the building with Charlie a million times, but we were always smart enough to kick open the warehouse doors. We would never go up the fire escape and in through the windows, because there’s no way to climb down the fifty-foot walls once you’re inside. You have to jump to an old catwalk and catch a ladder that way, which is probably how the Farley kid fell. It’s not an easy jump to make. Only Charlie has done it, and even he says, Never again.