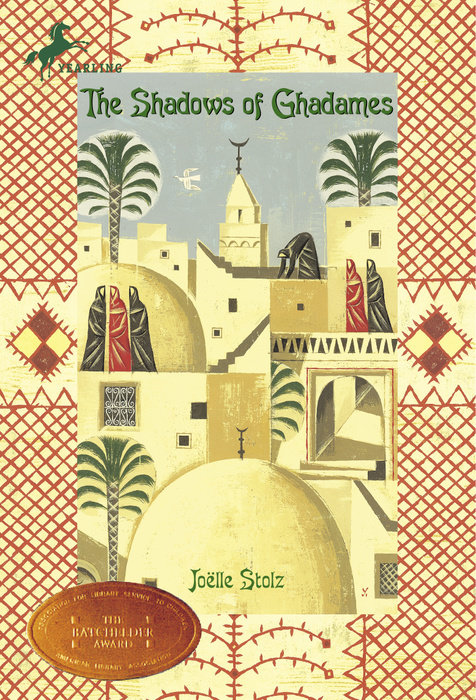

My father left on a trip early this morning.

This is our way of life in Ghadames. The men are often away on the desert tracks while the women wait for them on the rooftops.

But since this morning I can't stay still. I wander around the house, worried and tense, like an animal that senses a great windstorm is on the way.

Bilkisu woke me up before sunrise from a sound sleep. I had been rolled up in one of my mother's worn, soft and cuddly wool veils. I think I was dreaming of caravans. . . .

"Hurry up, Malika, if you want to say goodbye to your father!" Bilkisu says.

It is dark but I make out Bilkisu's smile as she leans toward me, her heavy silver rings pulling on her earlobes. And, above all, I recognize her smell, so unlike my mother's, a blend of jasmine and peppery spices.

Bilkisu knows I have a superstitious fear of letting my father leave on a trip without saying goodbye to him. If I fail…

My father left on a trip early this morning.

This is our way of life in Ghadames. The men are often away on the desert tracks while the women wait for them on the rooftops.

But since this morning I can't stay still. I wander around the house, worried and tense, like an animal that senses a great windstorm is on the way.

Bilkisu woke me up before sunrise from a sound sleep. I had been rolled up in one of my mother's worn, soft and cuddly wool veils. I think I was dreaming of caravans. . . .

"Hurry up, Malika, if you want to say goodbye to your father!" Bilkisu says.

It is dark but I make out Bilkisu's smile as she leans toward me, her heavy silver rings pulling on her earlobes. And, above all, I recognize her smell, so unlike my mother's, a blend of jasmine and peppery spices.

Bilkisu knows I have a superstitious fear of letting my father leave on a trip without saying goodbye to him. If I fail in my duty today, something dreadful could befall him.

"Hurry up," she says again more gently. "He's already in the kitchen, about to shut the grain storage container."

I scramble to the stairway leading to our rooftop. It is as straight and narrow as a rope ladder. I am so used to its steep incline that I can climb up even in the dark without falling.

Upstairs, I shiver from the cold--the desert cold at the end of the night, when not a single cloud protects human beings from the immense black sky.

Fortunately my mother has already lit a fire and sparks are flying to the corner of the roof. I like our kitchen, with its palm trunk beams worn by the smoke of the cooking pots, and its earthenware jars, covered with basketwork lids, for preserving food. And the convenient holes in the wall next to the hearth for the salt brought by caravan, one hole for the coarse gray cooking salt, the other for the fine white table salt that squeaks when you rub it between your fingers.

But, most of all, I like the grain storage container built into the corner farthest away from the fire; it is reassuringly potbellied, with a small round opening like a belly button.

"Good morning, my child."

My father greets me with a smile. His camel-hair burnoose is slung over his shoulders and his head is wrapped in a turban with the flaps floating around his neck. When it's time to leave, he will fold them over his mouth, as the Tuareg nomads do.

My mother does not look up. She is holding her measuring jar and counting in a low voice, taking out the amount of wheat and barley we will need for our meals during my father's absence. I hear the grain crackling as it rolls inside the wooden plates placed on the ground. Take exactly what's needed, that's our custom. We can feast and celebrate again only when the men return.

More than anyone else in Ghadames my mother, Meriem, insists on a strict adherence to traditional practices. I watch her in the glow of the fire as she divides up the grain and packs it down, with her fingers spread out. Her straight forehead, strong eyebrow line and delicate mouth are the features of a queen. She has bluish tattoos on her forehead and chin, and a mark in the shape of a star on each of her cheekbones. I know these tattoos have a magical significance, but I am not old enough yet for the women to explain it to me.

"Bilkisu," my mother says, addressing my father's second wife, "you can pour the barley into the large jar in the pantry."

Bilkisu picks up the plate. Though she never raises her voice, my mother has a commanding tone. Perhaps that's why I feel more at ease with Bilkisu, who treats me as though I were her own daughter. Bilkisu is tall and lithe, draped in indigo blue veils. She often laughs; when my father hears her, he can't help looking at her.

Her task accomplished, my mother lifts the plate filled with grains of wheat and holds it at arm's length. It is time to hermetically seal our grain container. Before sealing the opening, my father removes any putrid fumes that may taint the grain by slipping a burning wick inside the container.

For a brief moment, the glow of the flame outlines his angular jaw and his aquiline nose, and I feel a violent pang in my heart. I realize how much I will miss him during this trip, more than ever before. He straightens up, throwing the thick pleats of his burnoose behind his shoulder. Then he looks at me, his intense gaze making me feel like a real person, not like a child whom people caress without seeing.

"Look after yourself, Malika, and take care of your mother."

He has never spoken to me like this before.